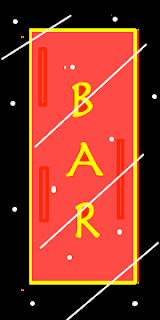

Through the falling snow and arm in arm under Gerry’s umbrella they walked up MacDougal Street, and within a matter of seconds, because this was Greenwich Village, a bar appeared on their right, and its vertical neon sign said, simply:

B

A

R

A hanging sign shaped like an oval bisected by a smaller oval elaborated:The

KETTLE

OF FISH

BAR

“I gather this is a bar,” said Araminta.

“So it would seem,” said Gerry.

There was a menu in the window.

“Oh, good – food!” said Araminta. “Shall we go in, mon cher Gérard?”

“I think we should,” said Gerry. “You see, Araminta, for me the best bar has always been the nearest bar.”

“This is why you are a philosopher, Gerry. But first –” She removed her arm from his and opened her purse. Gerry was a patient man, and he enjoyed the moment. Watching a pretty girl searching for something in her purse was more enjoyable than looking at a brick wall, or at a Picasso, or even at Picasso himself, whom Gerry had seen once long ago in Paris, sitting at a table at the Dôme with some other people who were possibly just as famous…

“Voilà,” said Araminta, and she brought out a fat hand-rolled cigarette. “Let’s fire up, old chap.”

“Oh, wait,” said Gerry.

“For what?”

“Araminta, may I ask if that is a reefer?”

“It most certainly is. We need to smoke a little gage, old bean, in order to heighten our gustatory delectation.”

Who was Gerry to say no? What had saying no ever gotten him?

“Splendid idea,” he said, and five minutes that felt simultaneously like five hours and five seconds later they were inside the door and Gerry was closing up his umbrella.

Yes, once again they were in Bar World, amidst the chatter and laughter and shouting of human beings, the swirling of smoke and the gleaming of bottles of liquor, the smells of beer and whiskey and perfume and aftershave, the sounds of what Gerry presumed to be jazz on a jukebox.

A half hour and a pizza with mushrooms and hot peppers later, sitting at a small table by the window with the snow still falling outside, two Bull Durhams lighted and a half-full pitcher of Rheingold on the table, Araminta said:

“Someday, when I am old, I will look back on this evening, and think, ‘I was young, and full of life.’”

“And I,” said Gerry, “when I am old, or I should say when I am older, I shall also look back on this evening, and say, ‘I was middle-aged, and as full of life as I ever was.’”

“If only,” said Araminta.

“Yes?” said Gerry.

“If only you were twenty years younger.”

“Yes,” said Gerry, “or, perhaps, if you were twenty years older.”

“Ha ha. But it wouldn’t be quite the same then, would it?”

“No,” said Gerry, “but nothing is quite the same as anything else.”

“What would you say, old bean, if I were to take you back to my flat and make savage love to you?”

“I should say that it might be quite embarrassing to have me suffer a myocardial infarction in your bed.”

“Yes, that would be a bother. Would you mind terribly if that happened and I dressed you and just dragged your body out into the hallway and let Mrs. Morgenstern deal with it?”

“I shouldn’t mind in the least. Although I doubt that Mrs. Morgenstern would be pleased.”

“A landlady’s work is never done.”

“Anyway, you have a boyfriend, Araminta.”

“Oh, yes. Terry. But he is so – inchoate, Gerry.”

“He’ll become less inchoate in time. Give him a few more years.”

“I don’t know if I can wait that long.”

“Most of life is waiting. And then when what you’re waiting for comes you start waiting for something else.”

“There you go with your philosophy again!”

“Yes, it’s a habit with me, and if I were a better philosopher I might be able to tell if it’s a good habit…”

“Didn’t you ever want to have any sort of job, Gerry?” asked Araminta, in that way she had of changing the subject without transition.

“No,” said Gerry. “Never.”

“And so you’ve never had a job?”

Gerry paused for a moment.

“Does being drafted into the army count?”

“I should think so. What did you do in the army?”

“I was thirty-two, completely out of shape, and completely lacking in militaristic spirit, however I had a degree from Harvard, and so the army in its wisdom gave me a desk job at Fort Dix. I shuffled papers, and read lots of books. When I was finally discharged in November of 1945 I had risen to the exalted rank of corporal.”

“So that was it, your one job.”

“I shuffled papers, and I shuffled them well.”

“Do you think I should get a job?” asked Araminta.

“Before I answer that, may I ask how you pay your rent and buy groceries at present?”

“My father pays my rent, and he also gives me an allowance of fifty dollars a month.”

“Then my advice to you is not to get a job.”

“I’m so glad you said that. I mean, what sort of job could I get, with a B.A. in English Lit from Vassar?”

“Nothing interesting, I’d warrant.”

“The other girls I graduated with have all gotten jobs on Vogue or Mademoiselle or Harper’s Bazaar.”

“I don’t see you working for a ladies’ magazine.”

“What about if I got on the New Yorker?”

“That might be better.”

“I could maybe write those little Talk of the Town pieces, about the city’s oldest doorman, or a good place to buy bagels.”

“Yes, but would you want to?”

“I could write a Talk of the Town piece about you, Gerry. A philosopher living on the sixth floor of a tenement at Bleecker and the Bowery.”

“Oh, I’m sure that would go over well.”

“Ha ha.”

“No, Araminta, you asked my opinion, and – bearing in mind that it’s coming from me and should be taken with several handfuls of salt – my opinion is that you should try to do as I have done, and never take a job if you can help it.”

“So just live off my allowance all my life?”

“Someday you’ll finish your novel, and it just might become a bestseller.”

“I doubt that.”

“Take it from me, Araminta. For three-and-a-half years in the army I worked in an office, and there wasn’t a second when I didn’t wish I were somewhere else. No, jobs are for those who have no choice but to work, or who have nothing better to do with the precious moments they have left on this planet.”

“What have I done to meet such a wise man as you, Gerry?”

“You moved into the same building that I live in.”

“A happy chance.”

“Yes, happy for me as well.”

Louie the waiter stood by the espresso machine smoking a Lucky Strike and gazing at that new odd couple sitting by the window, a man in his forties, a girl in her early twenties? What was their story? A father and daughter? Uncle and niece? If the guy was the girl’s sugar daddy, then why was he wearing that shabby old suit? It looked like a good cut, a Donegal tweed maybe, but it was twenty or twenty-five years old if it was a day, and the elbows were worn bald. The girl wore a black beret and a black sweater, straight black hair and red lips, and she was looking at the man like she was hanging on his every word. The man in his turn looked at the girl almost like he was shy. What was their story? Everybody who came in here had a story, and each story was different, just like Louie had his own story.

The man in the worn tweed suit turned and looked at Louie and raised his finger, but in a nice way, a kind of shy way. Louie put his Lucky in the ashtray on the shelf with the cups and saucers and went over. They wanted to know what was good for dessert, and he recommended the German chocolate cake with the cherry sauce.

{Kindly go here to read the “adult comix” version in A Flophouse Is Not a Home, profusely illustrated by the illustrious rhoda penmarq…”