We left our hero Arnold Schnabel with his new companion Sylvester T. “Slick” McGillicuddy here in a crowded bar called Bill’s Bar, in a place called Nowheresville...

(Kindly click here to read our immediately precedent chapter; if you’re looking for something to fill up the lonely hours of your life then you may click here to go back to the very beginning of this Gold View Award™-winning 69-volume autobiography.)

“I shall never forget that thrill I experienced when, on a rainy November afternoon in Philadelphia, the custodians of the Arnold Schnabel Society allowed me to hold in my silk-gloved hands and even ever so carefully to turn the pages of one of Arnold Schnabel’s original holograph black-and-white marble copybooks: such an unpretentious and neat Palmer Method handwriting, obviously done with Arnold’s favorite writing instrument, a common ordinary Bic pen, and with surprisingly few crossings-out and emendations – but what wonders, what infinite and magical worlds did those pages contain!” – Harold Bloom, in the Readers’s Digest Literary Supplement.

Great, I thought.

Nowhere.

Was this where I had finally wound up, at long last, after all my adventures and wanderings?

Nowhere.

Which was what he said again, annoyingly, the way most things are said when they’re repeated three or more times, which doesn’t stop people from repeating the same things over and over again. Repeatedly.

“Nowhere,” he repeated. “No where. At all. That’s where you are, pal. Not just at the end of the road, but at the place that no roads lead to and that no roads go out of. And not just a place that is no place but a place that is not even not a place, because to say that it was not a place would be only to say what it is not, when in fact it is what is not. Which is nowhere. No place. You get it? I mean, you comprende, kemosabe?”

Never had I felt more as if I was in a fictional universe. Real people just didn’t talk this way.

“Do ya hear that noise, man?” he said, shuffling a step closer to me, so that I could smell his breath, which smelled like all the cheap whiskey and beer and all the cigarettes in the world, mixed together and boiled down into a perfume that was the essence of death in life. “Do ya hear that dark noise banging around in the walls of your skull like a junkie locked up in one of them cold bare concrete junkie cells they got up there at Bellevue? Do ya hear that sound? Not the sound of that beat-up old piano over there banging out the sacred Negro ragtime, not the sound of these drunks in here laughing away their despair and their hatred of their lives, but the deep dark empty sound of nothingness, the sound of the death beyond death, the sound of the big empty big nothing.”

He had his “serious” look on now, the sweat pouring down his face as if there were a tiny sprinkler system installed under his dingy damp straw hat.

“Nowhere,” he said.

“Okay,” I said.

“But can you dig it, daddy-o?” he said.

“Not really,” I said, “but don’t worry, it doesn’t matter.”

“Oh, I’m not worried,” he said.

“Good,” I said.

“I ain’t worried. At least not about you I ain’t worried. Why should I worry about you? Don’t I got plenty problems of my own to be worried about?”

“I suppose so,” I said, and, yes, I was wondering how I could ever extricate myself from this conversation – or was this it? Was this to be my eternity, standing here forever listening to this irritating man in this bar in the middle of what might well be nowhere, if nowhere could even be said to have a middle?

“You suppose so,” said the Dan Duryea guy, after a pause which I suspected he meant to be taken as meaningful. And then – again, I guess he really did like to repeat himself, or at least to annoy people – he said, sort of cocking his head as he said it: “You suppose I got problems.”

“Just a supposition,” I said.

“Judging from my appearance and my manner.”

“Yes...”

“You say yes but it sounded like three dots in the air after you said it. Yes and what else?”

“Just the things you’ve said,” I said.

“You mean my litany of complaint.”

“Yes.”

“I’m really sorry I bore you.”

So was I, but I kept quiet about it this time.

“Okay,” I said. “Well, thanks.”

“For what?”

“For uh, telling me where we are.”

“Which is like nowhere, brother!”

“Right,” I said. “Thanks for, uh, filling me in.”

“Don’t thank me,” he said.

“Okay,” I said.

“I’ve only told you what anybody in this joint could tell you.”

“All right,” I said.

“But I thank you for your politeness, Archie.”

“Arnold, actually,” I said.

“I thank you, Arnold,” he said. “I thank you for saying thank you. It’s that kind of thoughtfulness which makes being caught in a whirlpool of deadly betrayal in a place that is no place just a little bit more bearable. Not a lot. But a little. So thanks.”

“You’re welcome,” I said.

“And there’s no need to say 'you’re welcome', neither. Again, I appreciate the sentiment, but it ain’t necessary.”

“Okay.”

“But thanks anyway for saying that. You’re welcome, Harold.”

“You’re welcome,” I said.

“I just said you didn’t have to say you’re welcome.”

“Oh,” I said. “Sorry.”

“No need to apologize.”

“Okay.”

“Although, again, I appreciate the – the politesse. You know what that means?”

“Politeness?”

“Yes. It’s like the way the Frogs say politeness. Except it’s somehow classier. And you, my friend, you got class.”

“Thanks?” I said.

“You’re quite welcome,” he said. “And I hope you enjoy your stay here in nowhere.”

He smiled, staring at me, and taking a drag on his Old Gold. He seemed to be waiting for me to say something, but I didn’t want to say anything to him, except maybe goodbye. I wanted just to walk away, but where could I go? If this really was nowhere, did that mean there was nowhere else to go? And if I just went down to the other end of the bar, as I had already suggested I might do, I would probably then only meet some other unpleasant person, maybe someone even more unpleasant than this guy.

“Slick” continued to stare at me through his cigarette smoke as these thoughts worked their way through the spongy mass of my cerebral matter.

And then, like most people, he couldn’t stand not to say something when no one else was saying anything, so he said, again, articulating the syllables in an annoyingly exaggerated way:

“No. Where.”

He smiled again. He seemed very pleased with himself.

“Or let me phrase it another way," he said. "Would you like me to?”

“Yeah, sure, uh –”

“Slick,” he said. “Call me Slick.”

“Sure, 'Slick',” I said.

“No,” he said. “Place.”

Again he was smiling.

“Get it?” he said.

“Yes,” I said. “I get it. As you’ve explained to me, we’re nowhere. No place. Nowheresville.”

“Very good!” he said.

Now he stopped smiling.

“You seem to be taking it very well,” he said.

“Would it help if I didn’t take it well?” I said.

“No, it wouldn’t,” he said. “Although, just a suggestion, it might make you feel ever so slightly less miserable if you cried in your beer, just a little.”

I realized I was still holding the schooner, and that there was still beer in it, perhaps a third of a pint. I didn’t want to cry in it, but it seemed a waste to let it get warm and flat, so I raised it to my lips and drank it down, all of it, then I laid the empty schooner on the bar, and sighed.

“So you’re a sigher,” said Slick.

“A what?” It had sounded to me as if he said “sire”, which made no sense, even less sense than what he had been saying.

“You sigh,” he said. “Sigh. Like an exhalation of resigned acceptance of one’s fate. A sigh.”

“Oh, right,” I said.

“I’m guessing you sigh a lot, my friend.”

“You have guessed right,” I said.

“Let me ask you something, though, if I ain’t prying.”

“Sure,” I said.

“What the fuck have you got to sigh about?”

“I’d rather not talk about it,” I said.

“Don’t get all superior with me. Don’t be acting all like your shit don’t stink just because you don’t talk about yourself all the time.”

“All right, I said. “I sigh because ever since I woke up this morning I have had dozens of bizarre adventures in various dimensions and worlds, including what is perhaps incorrectly called ‘the next world’. I have wandered in and out of half-a-dozen fictional universes, several of them in the company of a talking fly named Ferdinand. I have spent time in the company of the son of God as well as the prince of darkness. I have been attempting for what seems like at least four years now to return to what I like to think of as my own world, or the real world if you will, but with absolutely no success, and in the last world I was in I became so frustrated with the people I was with, including a talking dead colonel in a painting, that I dove, arms outstretched, like a diver or like Superman, straight into the screen of a large Philco television set. I came through the screen and wound up here with you in this bar. And everything is in black and white. And now you tell me we are nowhere. So these are just some of the reasons why I sigh. I have plenty more, but I don’t want to bore you, or, even more so, myself, by recounting them.”

He stared at me for a moment after I had finished my little diatribe. Then he lifted up his own schooner of beer. It was still about half full. Or half empty. Anyway he raised it to his lips and drank, his Adam’s apple bobbing in his throat, and when he put the schooner back down on the bar it was completely empty. He wiped his lips with the sleeve of his dingy white suit-jacket. He had been wearing his serious face, but suddenly he smiled, brightly, or brightly for him.

“Another beer?” he said.

“I don’t want another beer, thanks,” I said.

“Don’t thank me, Charlie,” he said; I didn’t know if he had forgotten my name again and thought it was Charlie, or if “Charlie” was just an annoying name he called people. I said nothing to fill up the ensuing conversational chasm, so after half a minute he elaborated: “Don’t thank me. Because I wasn’t offering to buy you a beer. Because it’s your turn to buy, my friend.”

“Well, I’ll buy you one,” I said, “but I still don’t want another one for myself.”

“How about a shot?”

“I don’t want a shot either,” I said.

“I didn’t mean a shot for you, Charlie baby.” Yes, he really did think my name was Charlie, but I didn’t care. He could call me Beelzebub for all I cared. “No,” he went on, after realizing I wasn’t going to ask him what he meant (because I didn’t care what he meant), “I meant a shot for me.”

“Okay,” I said. “Sure. I’ll buy you a shot. Provided I have any money on me.”

“You mean you don’t know if you got any money on you?”

“I can’t be sure,” I said.

“Check your wallet.”

I started to pat my pockets, for some reason starting with my jacket pockets, and I felt something hard and heavy in the right one.

“That’s odd,” I said.

“What’s odd? You ain’t gonna say you lost your wallet, are ya?”

“No,” I said. “It’s just there’s something in my pocket.”

“Let me see.”

I reached in to the pocket. It felt like a pistol. I brought it out. It was a pistol.

“A gat!” said Slick.

“I know,” I said.

“Put that thing away!”

I put it away.

“What’re you doin’ walkin’ around with a gat? Don’t tell me, Richie the Rat Ricciutto sent you, didn’t he?”

“Not that I know of,” I said.

“Not that you – oh, I get it. Richie didn’t want you to give it to me fast, which is why I’m still alive right now. He don’t want to make it quick. You’re supposed to take me out of here, right? To the basement of Richie’s restaurant, Fra Diavolo’s. Where him and the boys can grind me up into meatball meat. But slow. Real slow. Is that it?”

“No,” I said. “I remember now. This lady named Lily gave it to me.”

“A lady named Lily.”

“Yes,” I said. “She had this roadhouse where she sang and played piano.”

“Lily’s Roadhouse?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Except the neon sign is partly busted, so it looks like “L S ROADHOUSE”?”

“So you know the place.”

“Sure I know it. Nice stoppin’ place. Lily and Laughing Lou. Good people.”

“Well, anyway,” I said, “Lily gave me the pistol.”

“How come?”

“I think to protect me from Laughing Lou.”

“Okay, so maybe Laughing Lou ain’t such a nice guy. Don’t ask me to get mixed up in any beef you got with Laughing Lou, okay?”

“I won’t,” I said.

“I got my own problems. So what about that beer and shot you were gonna buy me?”

“Oh, right,” I said, and I lowered my hand to pat my rear back pants pocket, which is where I normally carry my wallet, but now someone put a hand on my forearm, stopping it in its progress, and a woman’s husky rich voice said:

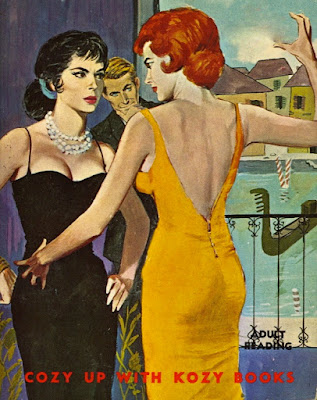

“Your money’s no good here.”

I turned, and it was a beautiful tall woman. She had long shiny wavy blonde hair to her shoulders, anyway I assumed her hair was blonde, although I couldn’t be sure, as everything was still in black and white. She seemed somehow familiar, but not like someone I knew, more like a movie star whose name I couldn’t remember, or never knew in the first place.

“Hello, Arnold,” she said.

(Continued here, and onward, at the same stately but thorough pace.)

(Please look to the right-hand column of this page to find a rigorously-current listing of links to all other legally-released chapters of Arnold Schnabel’s Railroad Train to Heaven©; pre-order now for your own Railroad Train to Heaven™ hand-made artisanal action figures, the perfect stocking-stuffer for Christmas, Hanukkah, Kwanzaa, or atheist or nondenominational mid-winter celebration.)